A few blackberries hang low on the bramble, the deep indigo light drawing me in like a magpie to darkest jewels. I touch one, pulling at it gently to release it from the plant. Its small body lies in the palm of my hand, warmed by the morning sun and I marvel at how one single berry feels so heavy and full. I continue on my walk leaving the blackberries to soak up the days sun in their home by the constant whirring of the bed factory. A small trackway leads out of the housing estate where spears of mugwort have escaped the strimmer and a bag of clothes have been dumped, a child’s pink fluffy nightgown pulled from the bag now lying like an empty skin across the path. I cross over the railway where field bindweed creeps about the red bricked bridge, upturned striped candy pink parasols all reaching for the sun. Now which way? I always think I know where I’ll walk until I begin and then I realise how I want to go everywhere, see everything so I ask out loud ‘Now which way?’ and I wait for the answer. A field of barley ahead moves in a slow motion wave as its pulled by the breeze in an easterly direction, so that’s where I walk following the barley that dances as if someone is painting it into the landscape just one step ahead of me.

I walk the field path with the railway next to me and turn left at a small junction. Here a hedgerow runs between the fields, just 250 meters long with a central footpath that nobody ever uses. In winter the path is mud with a deep unquenchable thirst and in late spring it cocoons itself in cow parsley and stitchwort until the nettles, wild carrot and bindweed appear to create a fortress of growth. Today hops are beginning to find their way over the dried hogweed heads. They travel on a single sinewy thread which if you run your fingers against reveal velcro like feet that journey far over the hedgerow much like their latin namesake , Humulus Lupulus, ‘Wolf of the woods’. There are many things in nature I try not to associate with humans as after all we do like to feel that so much is here for our own benefit but hops to me are a relationship I can’t ignore, so many hands from so many ages have harvested this crop and I wonder at the stories told as they did so. My husbands Romany family were some of those killed in the Hartlake disaster whilst coming home from a day of hop picking, the wolf followed them as they headed home that stormy night. Today the hops are still a way from harvesting, the flowers are at the very beginning and hang gracefully as tight vivid green droplets. I scrunch one in my fingers and it smells so strong already, bitter and beer like. A dragonfly catches my attention as it hawks the path and I follow it up the hedge line.

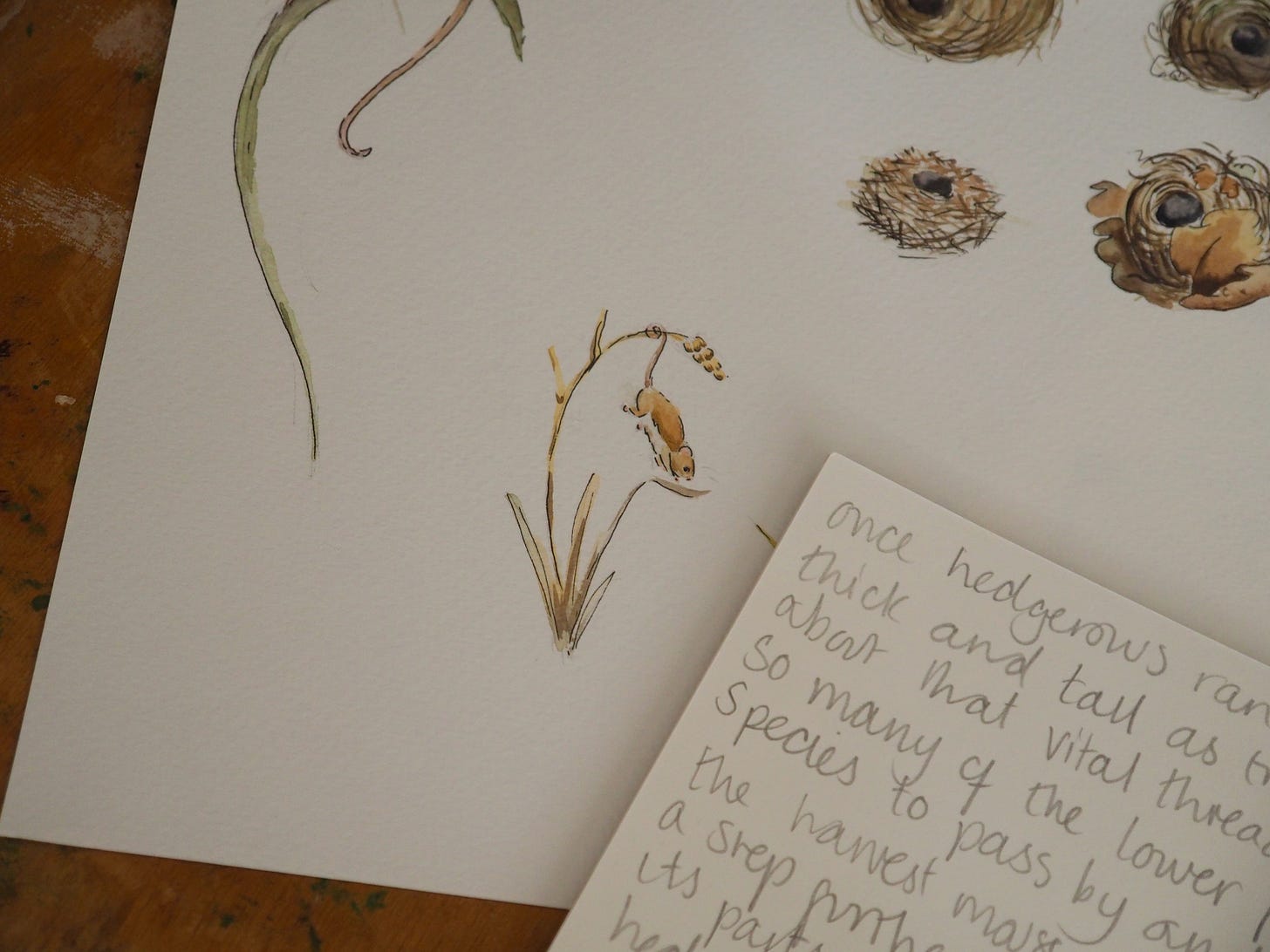

I talk to this hedgerow sometimes both internally and audibly if alone. Though I am never really alone here as harvest mice live in this small 250 meter stretch. Micromis minutis, the suffix says it all. A minute mouse as golden as the corn it loves. In my humble opinion it is one of the most beautiful of small mammals with its curling tail like that of the hops and a short stubby muzzle that makes it appear kinder than some of its cousins. Try as I might though I cannot get the landowner to see the beauty of these creatures and each year the hedge is cut down to sharp stubby teeth. During lockdown it was left untouched for two seasons or more and the hedge was a song of life until the machine came back and I spent a whole morning picking up armfuls of their nests, I have not seen them in that number since.

Harvest mice nests are perhaps just as enchanting as the creature itself, an intricately woven structure developed through night time acrobatics as each mouse steadies itself with two blades of plant life before pulling each piece of grass in individually, twisting it and weaving it to form a nest around its body, with a single circular entrance hole it is the perfect creation. The solitary summer nests no bigger than a golf ball, close and cosy with the summer breeding nests being the size of a tennis ball, the grass in its nature allowing for expansion as the litter grows. When fields were once cut by hand these little mice would often be bundled up with the grain and returned home to the stores where they would over winter having no need to leave with a human sized larder at their disposal and its thought that is where the name harvest mouse comes from as they come in with the harvest. Now though they go to ground in winter hoping to find warmth from the earth and safety from machines. At night when I can’t sleep I often trace my footsteps down to this spot and when I’m here in the dark I step into the hedgerow and become just an eye without a body, I see it all at the same height as a mouse. I feel the shadows of the leaves overhead and the cool night breeze that has made it through. I hear the tiny teeth of the harvest mouse as it eats and the air shift as an owl hunts above. I never see a mouse, even in this imagined space but its enough just to know they are there and somehow it always helps me to sleep.

Once hedgerows ran across the countryside as thick and as tall as trees and I think about that vital thread that allows so many of the lower food chain species to pass by and I think about the harvest mouse taking that thread a step further by physically weaving it’s parts. Scientifically to lose a hedge is to lose so many things but try as I might my mind has never quite grasped science. Instead my mind wonders at the other things, I wonder at the wisdom we lose. The grandmother voice of warp and weft so tangible it can be tasted in a good hedge. Things are stronger when they are stitched, we know this so what does it mean to live in a land unpicked? I do not know the answer but I will sit here and listen for the voice of one minute mouse in the land of woven green.

I felt like i was there with you. Loved it.😊

Just beautiful ❤️